A seasonal story set in 1926. John is staying with his wealthy college friend Lawrence for the Christmas holidays–and desperately trying to hide his feelings for him. He’s beginning to think it might have been a bad idea…Written for the 2011 Speak its Name advent calendar.

A seasonal story set in 1926. John is staying with his wealthy college friend Lawrence for the Christmas holidays–and desperately trying to hide his feelings for him. He’s beginning to think it might have been a bad idea…Written for the 2011 Speak its Name advent calendar.

Daylily

“I say, John, have you seen the paper?”

Busy cutting a mount for his host’s Christmas gift, a photograph of All Saint’s College, Cambridge, John didn’t look up. “It’s in the window bottom.”

“No, it isn’t,” was Lawrence’s retort. “It’s in my hand, as a matter of fact. I was asking whether you’d read it, not if you knew where it was, idiot.”

At that, John did look up. “Can’t see as how I’m the idiot when it’s you that can’t express himself clearly.” He hoped his tones were as gruff as usual, but somehow he always found himself softening when he looked at Lawrence, with his fine-boned face and outrageously wavy hair. “So what’s in this paper, then, that you’re so mithered I should see?”

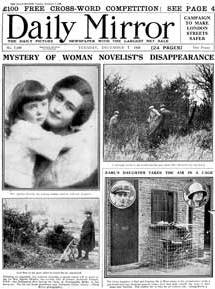

“Mrs Agatha Christie—yes, John, the Agatha Christie—has disappeared. They found her car abandoned somewhere in Surrey, and eighty policemen have been combing the area in search of her.”

John snorted. “Likely she’s another novel about to be published, then.”

Lawrence laughed. He was lolling on his stomach on the lionskin rug in front of the fire—something John would never have dared to do in his own father’s house. Then again, the rugs in the house John had grown up in had been well-trodden, comfortless things made years before by his mother, and the house itself so small that if you lay on the floor like as not the whole family would have fallen over you before lunch. Lawrence’s house was so big you could go all day without seeing your family, save at mealtimes.

Lawrence was in shirtsleeves, tieless, his shirt open at the neck, and John wondered how on God’s green earth he was ever going to survive this visit without giving himself away. It was bad enough at college, where they shared a set—but here, where Lawrence seemed almost sinfully relaxed and comfortable…

“Why don’t you come down here and read it with me? You must have finished Father’s present by now.” Propped up on both elbows right next to the lion’s head, Lawrence gave a winning smile. Maybe it was just the contrast with that gaping, toothed maw, forever roaring its defiance at the hunter who’d bagged it, but Lawrence’s pale, beautiful face looked even younger and more innocent than usual to John’s guilty eyes.

“I’m fine where I am,” he muttered shortly.

Lawrence pouted. “Don’t be such a spoilsport. Come on, Johnny, it’s lovely and warm down here.”

Much against his better judgment, John lowered himself down beside his slender companion. It was warm down there—a little too warm, in fact, but John didn’t think the fire was to blame. “So go on—show me this article, then.”

Beaming, Lawrence shifted the newspaper over so John could get a better look. “See here? It says her car was found by a young gypsy boy, right on the edge of a quarry. She’d left her driving licence in it—and her fur coat. Now tell me, would any woman have done that if she’d had any choice in the matter?”

“Maybe it was a warm night?”

“In December? She was in Surrey, not the Cote d’Azur. It’s my belief, Professor Higgins, they done her in.”

John laughed despite himself. “Oh, aye? And who would they be, in this particular instance?”

“Oh, the Colonel, of course. Cherchez l’homme. Perhaps he was jealous of her success—after all, what man would enjoy having a wife more celebrated than he is?”

“You wouldn’t want a successful wife, then?” John asked, and held his breath for the answer.

“Oh, Lord, no! In fact, I wouldn’t want—” Lawrence broke off as the door opened and a tall, ponderous man with prematurely faded brown hair walked in. “Oh, hullo, Geoffrey. I didn’t realise you were back. This is my friend John, from college—John, may I introduce my brother, Geoffrey?”

John scrambled to his feet, embarrassed at having been caught rolling around on the floor like a guttersnipe. “How do you do?” he mumbled, his cheeks burning.

Geoffrey gave him a curt nod, ignoring his outstretched hand. “Lawrence, I want a word with you. If you’ll excuse us, Mr…?”

“Walker. John Walker. I’ll, ah, wait outside.” John made stiffly for the door.

“For heaven’s sake, Geoffrey,” Lawrence complained petulantly. “Do you have to be so damned rude—” The shutting door cut off his tirade. Breathing hard, John stood for a moment by the door, then became aware of a maid looking at him curiously. Heat rising anew in his face, he nodded to her much as Geoffrey had to him scant minutes ago, and strode off stiffly down the corridor.

More by luck than by judgment, John found his way to an outside door. Flinging it open, he stomped outside and breathed deeply of the frigid December air.

“Welcome to Whiteheys,” a gravelled voice said from nowhere in tones drier than a temperance meeting.

Startled, John spun around, to find himself facing… He blinked. This could be Lawrence—if Lawrence had aged thirty years in the last ten minutes. The same slight frame, the same wavy hair, the same high cheekbones and blue eyes—but the eyes were dull, the hair faded straw, not golden, and the elfin grace of Lawrence’s figure had become the angular gauntness of ill-health. John had a fleeting fancy he’d somehow strayed into some grotesque Wildean nightmare. The man’s cheeks hollowed as he drew upon a cigarette—only to suffer a fit of coughing that racked his bony frame so violently John was shaken out of his paralysis. He leapt forward to offer the man some support.

“Are you all right? Should I fetch someone?”

The old man waved his hand in a negative as the hacking cough subsided. “No, no. It’ll pass.” He gave the cigarette a rueful glance, and let it fall to the ground. “So, you’re the belle de jour, then?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“The daylily, which blooms at dawn, only to wither by sunset.” He gave John a glance that seemed to combine amusement and pity, the hard lines around his pinched-looking mouth a witness that it was more used to swear than to smile. “Must I speak plainly, then? My nephew’s current amour. I must say, you’re an improvement on the last five or six—they really weren’t comme il faut. His last, if you’ll believe me, was a tailor’s apprentice!”

“The daylily, which blooms at dawn, only to wither by sunset.” He gave John a glance that seemed to combine amusement and pity, the hard lines around his pinched-looking mouth a witness that it was more used to swear than to smile. “Must I speak plainly, then? My nephew’s current amour. I must say, you’re an improvement on the last five or six—they really weren’t comme il faut. His last, if you’ll believe me, was a tailor’s apprentice!”

“His…” John couldn’t go on. Had he been so mistaken in Lawrence? He’d thought him too naive to understand the effect he had upon John. Had this seeming innocence been jaded indifference all along? Had he laughed at John, amused himself by stringing him along with studied gestures? And the invitation to stay for Christmas—what had that been about? Had Lawrence planned to entertain himself with an easy seduction—and then discard John as he apparently had all the rest?

No. He was damned if he’d believe it of his friend. “You’re mistaken, sir,” John said roughly.

“Oh, I don’t think so.” The old roué smiled. “I’ve known Lawrence since he was in short trousers—such a pretty little thing he was, too.”

The smile, in John’s eyes, turned sinister and predatory. The garden’s air was no longer fresh and crisp with the promise of snow, but heavy and fetid. It suffocated him. “I have to go,” he forced out, and fled back into the house.

“John!”

John ignored his friend’s cry, unable to face him just yet. He ran up the stairs to the guest room assigned him, where he flung himself face down upon the bed.

A moment later, ashamed of such melodrama, he rose and went to stare out of the window. The old man, he was relieved to see, was nowhere in sight—the view consisted of only the bare trees, seeming more dead than alive in their drab winter’s garb; the damp earth; and the mist rising off the lake.

It made so much sense, he realised. No one could be so naive, so guileless as Lawrence had acted. But God, had his uncle really been implying–

There came a hesitant knock at the door. When John failed to answer, it opened anyway.

“John, what on earth is wrong?” Lawrence asked. From his rigid stance at the window, John heard light footsteps enter the room. There was the sound of the door closing behind him. “If it’s something I’ve done—”

“Someone, more like!” The vicious words burst from John’s lips, unstoppable as the tide.

There was a moment’s shocked silence. Then: “Someone’s been talking to you, haven’t they? Who was it? Not Geoffrey, he’s been lecturing me on indolence and profligacy all this time. Father? Or—no. You met Uncle Alfred, didn’t you? Oh, God. Geoffrey told me he’d brought him. Lord knows why—he must know nobody wants him.”

“Is it true?” John asked roughly, turning to face the object of his foolish desire, the anger of humiliation like acid in his stomach. “Have you been laughing at me all this time? The uncouth Northerner, who thinks you such an innocent he’ll not lay a finger on you? Has it been fun, watching me bumble my way around you, trying to hide the way I feel?”

Lawrence reacted as if John had stabbed him, taking a pace backwards, his face pale. “What—” He broke off, his voice cracking. “It’s not true. Not of you. I swear—”

John stared into that beautiful face, begging Lawrence wordlessly to give him some reason, however small, to dismiss the allegations as baseless slander. “Why should I believe you?”

Lawrence gave a pained-looking smile, his eyes the picture of despair, and John’s hopes faded. “You shouldn’t, really, I suppose. What did he tell you? That I’d had scores of lovers? It’s true enough.”

It was as if a great crack had opened through the centre of John’s heart.

“I thought…I thought that was the way of it,” Lawrence carried on. “For men like us. That’s what he told me.”

John found his voice. “He? Who?”

“My uncle, of course. Who do you think was my first?” Lawrence’s gaze was steady, only the tremble of his lips betraying him.

John’s heart shattered, taking his anger with it. He found himself striding forward, grasping Lawrence by the arms, holding him gently. “How…were you very young?”

“Young enough, but does it matter? I swear, John, there’s nothing like that between us now. There hasn’t been for years.” Those blue eyes were wide and pleading.

“Did you… love him?”

“I thought I did. He was different, then, John—the last few years haven’t been kind to him. When I was home from Eton one summer I begged him to run away with me, to go to the Continent where we could live together more freely.” A bitter smile twisted Lawrence’s lips. “That was when he told me how ridiculous I was being, how two men could never fall in love like a man and his wife. I thought I was doomed to a lifetime of brief trysts.”

“So why not tryst with me? You must have known I wanted to—” John coloured.

“Because you’re my friend! I didn’t want some… sordid release from you. I wanted you… I wanted you to love me.” Lawrence hung his head. “I really thought you might. I thought… if you didn’t know I was… soiled, it could be as if we were discovering things together. I’m sorry.”

It was a moment before John could speak, and when he did so, his voice was gruffer even than its wont. “Is that how you think I see you?” he asked. “As… soiled?”

Lawrence hung his head.

“You’re not,” John told him firmly, taking Lawrence’s face between his hands and lifting it gently. “You’ve just not been well looked after, that’s all.” He smiled. “You won’t need to worry about that any more.”

***

Ten days later, the lionskin rug was once again occupied. The door was locked against all unwelcome brothers and uncles, and a chair wedged under the handle to boot, though Lawrence had laughed this excess of caution. Lawrence lay on his stomach reading the paper once more, but this time John lay comfortably beside him, an arm slung around his lover’s waist, a hand occasionally creeping lower still. “So they found her, then?”

Ten days later, the lionskin rug was once again occupied. The door was locked against all unwelcome brothers and uncles, and a chair wedged under the handle to boot, though Lawrence had laughed this excess of caution. Lawrence lay on his stomach reading the paper once more, but this time John lay comfortably beside him, an arm slung around his lover’s waist, a hand occasionally creeping lower still. “So they found her, then?”

“Mm. Apparently she’s lost her memory—how awful. There could be whole books, lost forever! The intricate workings of M. Poirot’s little grey cells vanished like a will’o’the wisp, never to be heard of again.”

“It’s still better than what you thought, that the Colonel had done her in.”

“Very true. See, I admit it, when I’m wrong.”

“And I don’t?” John said, propping himself up on one elbow and turning to face his friend. With his free hand, he traced the contours of his lover’s face. To John’s amusement, Lawrence closed his eyes and leaned into the caress, for all the world like a pampered pet cat. John half expected him to start purring.

“Not willingly,” Lawrence murmured. “One has to prise the admission out of you with a crowbar.”

“I’ve never disputed I was wrong about you.”

“About me being such an innocent, you mean.” Lawrence’s voice was quiet, but the bitterness was still unmistakeable.

“No, you great daft jessie. I meant, when I believed what that old devil told me.” John smiled. “And you were innocent, you know. In your heart, you were. All that time—” he still couldn’t quite bring himself to say All those men, and perhaps never would “—and you’d never known love.”

“Ah, but I know it now, don’t I?” Lawrence sighed in contentment. Their kiss, when it came, was warm and comforting, and tasted of hot spiced wine, chocolate coated cherries and mince pies, and promises for the night to come.

“That you do,” John said gruffly, pulling his lover closer still, his heart so full of joy it threatened to burst. “And I’ll not let you forget it.”

![locknut_200x300[4]](https://farm1.staticflickr.com/904/40247243490_3a97895e2a.jpg)